The paramedics worked feverishly on Manisha to make sure she was still alive. My beautiful seven-year-old daughter from Nepal lay on the floor unconscious at the O’Connell Center of the University of Florida.

“Has she ever had a seizure?” another one asked?

“No, no,” I said in bewilderment. Manisha rolled over and vomited.

One emotion consumed me: Fear. The enormity of single parenting hit me like lightning.

I cried out, “Where are you, God? I feel so alone.”

After hooking up stabilizing IV’s, Manisha was whisked off in an ambulance to Shands Teaching Hospital. I found a pay phone and called my mother. Her first comment was, “Do you know what day this is?”

I remembered—September 19. Four years to the day and almost to the hour, my father had died of a brain tumor. It was about 5:00 p.m. My shattered world continued to close in on me. A short time later my worst fears were confirmed.

“There is something on the CAT scan. We have a called a neurologist,” I heard the nurse say.

“No, no, no,” every cell in my body cried out. “God, you can’t let this happen. Not again!”

But God was silent. The next nine days of hospitalization were filled with tests—MRI, gallium scan, spinal tap, TB test, HIV test, numerous blood draws, and too many questions and not enough answers by doctors doing their daily rounds with medical students in tow. Manisha had what in medical parlance is called a “zebra.”

As the days passed in the hospital, I asked God for two things that humanly speaking seemed impossible. I prayed first that the doctors would not have to do surgery. I couldn’t bear the thought of seeing Manisha’s beautiful thick, curly black hair shaved off. The ugly scars of surgery still lingered in my mind from my dad’s brain surgery. And I prayed that whatever was in Manisha’s head would not be cancerous. I had asked God to heal my father of a brain tumor and he died. Could I trust God for Manisha’s healing?

The next year we learned how to live a new normal as we adjusted to the reality of seizures. Questions concerning the correct diagnosis lingered. Following another seizure and a questionable MRI a year later, we traveled to Connecticut so Manisha could be personally examined by one of the world’s leading experts in pediatric infectious disease at the New Haven Hospital, Yale College of Medicine. Dr. Margaret Hostetter put together a team of scientists to consult on Manisha’s case, including Dr. Patricia Wilkins at the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta and Dr. Clinton White, Chief of Infectious Disease at Baylor College of Medicine. The diagnosis had been narrowed down to two things: The lesion on the MRI was either a cancerous brain tumor or something known as neurocysticercosis. While both are monsters, I hoped that it was neurocysticercosis because anything was better than cancer—even a parasitic infection.

Manisha had been adopted by me from Nepal at the age of three—old enough to be exposed to the extreme poverty of Nepal and the lack of clean drinking water. 57.1 percent of the water in Nepal is considered unsatisfactory for human consumption, and contaminated with feces, according to a paper written by Kiran Sapkota, MS, which will be presented in November 2009 at the Annual Meeting and Expo sponsored by the American Public Health Association.

Neurocysticercosis is the most common parasitic infection of the nervous system. It is caused by the larvae of the tapeworm, Taenia solium, normally found in pork. The eggs of the tapeworm are shed in stools and then ingested. The eggs end up in the stomach where they lose their protective capsule and turn into larvae. The larvae can then travel anywhere in the body—the muscles, brain, eye, and other structures. Years later, when the larval cysts die in the brain, edema occurs which sets up an inflammatory response in the form of seizures. In Manisha’s case, the worms would have traveled from the intestines to her brain where they died, causing edema and infection. It was hard to believe that something that foreign could live inside her little body and cause seizures almost five years later.

Neurocysticercosis is still a relatively rare condition in this country, but increasingly is appearing on the radar as part of the differential diagnosis for seizures because of the increase in international travel from third-world countries. As more children are adopted from Nepal and other poor, impoverished nations, adoptive parents need to make sure their children are dewormed as soon as they arrive. Had Manisha been dewormed, the eggs, larvae, and any worms in her body would have been killed.

Thankfully, eleven years later, Manisha is a well-adjusted 18-year-old just finishing high school and taking college classes. While the doctors at that time were never able to confirm she had neurocysticercosis, they were able to eliminate every other cause and felt with reasonable medical certainty that is what she had. Even a new, more sensitive test developed by the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta was negative for neurocysticercosis. I had to trust God not to worry and trust the doctors with their medical expertise. Now, having been seizure-free for over eight years with no other symptoms, the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis is certain.

Why did God allow this “nightmare” to happen? I don’t know why God allows the hard things in our lives, but I do know God never wastes anything. Everything in our life He uses to draw us to Himself if we will listen to His voice inside of us. I hope writing about neurocysticercosis today with sound an alarm for all international adoptive parents to seek appropriate medical care for their newly adopted children from Nepal. Neurocysticercosis is treatable and oftentimes a preventable condition with awareness and deworming upon arrival.

Proverbs 13:12 says, “Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but when dreams come true at last, there is life and joy.”

I claimed Proverbs 13:12 when I adopted Manisha from Nepal, and I gave her the middle name “Hope.” That night when Manisha lay in the emergency room when all hope seemed lost, I quoted this passage to the doctors as they worked on her. Later that evening as Manisha peacefully lay in her hospital bed and my heart was so heavy, God spoke to me in an almost audible voice. He said it twice: “Manisha will be okay. Lori, Manisha will be okay.” My only regret is that I wasn’t a better listener.

My faith was severely tested. I learned how weak I am and how much God’s word means to me. I learned how much my Christian friends loved me. I learned the meaning of prayer and its power in my life. I learned to live one day at a time, sometimes one hour at a time. I learned never to take my children for granted. They belong to God. I learned to have more compassion for others going through severe trials. I learned no matter what happened, my love for God would never waiver. If God was all I had, God was sufficient. And most importantly, I learned where there is life, there is hope.

I did not believe God brought Manisha here from half a world away only to die at seven. God’s hand was on her and He brought her here for a far nobler purpose. When calamities face us and fears overwhelm us, may we remember that God is greater than all our worries. He will never leave us or forsake us. He will always be there.

As I reflect on how hard the teenage years have been, I am reminded of God’s faithfulness in bringing my daughter to me from Nepal and healing her from the horrors of seizures. In spite of the trials of single parenting, the years following that dreadful day of September 19, 1994, have been filled with life and joy just as I quoted to the doctors that night when she lay on a gurney hooked up to I.V.s. Manisha soon will be leaving home to make her own way in the world and I reflect on her middle name Hope—with God, there is always hope, and for that I am thankful.

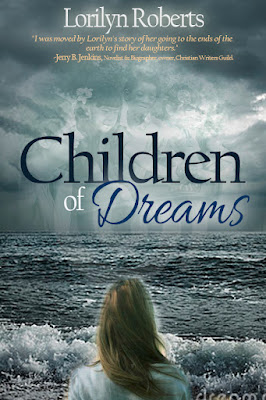

For more on Manisha’s story, read Children of Dreams, available at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and your local bookstores.

No comments:

Post a Comment